The Founding of the Police Association of New Orleans (PANO)

The Police Association of New Orleans (PANO), established on July 28, 1969, at the Police and Fireman’s Holy Name Society Hall at Our Lady of Guadeloupe Church, was the first police union in the Deep South. The fourteen founding members—Irvin L. Magri Jr., August A. Palumbo, Vincent J. Bruno, Joseph Gallodoro, Lester Carr, Curt Lechler, Louis Munsch, Justin "Skeeter" Favaloro, Tommy Leggett, Addison R. Thompson, Louis Jefferies, Xavier Viola, Jules Crovetto, and Lynn Schneider—created PANO to address critical issues faced by New Orleans police officers, including poor working conditions, substandard pay, and low morale. At this historic meeting, Magri was elected PANO’s first president.

Despite resistance from city leadership, PANO’s formation ignited a transformative wave across the South, influencing not only municipal governments but also major labor movements. PANO rapidly grew, expanding from fourteen members to 750 within four months, demonstrating the widespread frustration among officers. Its mission was clear: to fight for better salaries, improved working conditions, and fair representation for the patrolmen and sergeants who formed the backbone of the New Orleans Police Department.

Early Struggles and the Fight for Recognition

At the time of PANO’s founding, police patrolmen earned $530 per month, with state supplemental pay of only $16 to $50 based on years of service. PANO demanded an increase in base salary to $900 per month, modern equipment (including first aid kits, shotguns, and rifles), improved station facilities, and equitable overtime policies. Many district stations were condemned, uniform allowances were insufficient, and morale was at an all-time low.

The union’s first major action came on November 7, 1969, with the "Blue Flu," a sick-out involving over 600 officers. This protest, coinciding with a general election, saw the New Orleans Fire Fighters Association join briefly in what was dubbed the “Red Flu.” The city’s response was harsh: police officers were subjected to home inspections by internal affairs personnel and medical exams at odd hours. When the fire department fired 68 firemen for their participation, the firefighters’ union withdrew support, but PANO stood firm.

Superintendent Joseph Giarrusso, a staunch opponent of unions, sought to dismantle PANO by transferring its leaders to dangerous walking beats without radios. In a bold countermeasure, PANO mobilized off-duty officers to accompany their colleagues on patrol, effectively transforming crime-ridden Dryades Street into one of the safest areas in the city. This unexpected show of solidarity forced Giarrusso to reverse his orders, marking a significant victory for the union.

Landmark Achievements

In 1973, PANO secured the first collective bargaining contract in the South. The union continued to grow despite persistent harassment, such as punitive assignments for union leaders. Magri and other PANO executives endured ongoing attempts to undermine their work, yet the union thrived, inspiring police departments across the region to organize.

Vincent Bruno succeeded Magri in 1975 after Magri was fired for criticizing the administration. Bruno led PANO through the tumultuous 1979 police strike, which canceled Mardi Gras for the first time since World War II. The strike highlighted deep divisions between officers and city leaders, but it also demonstrated PANO’s growing unity and resolve.

In 1980, Ron Cannatella became PANO’s president and focused on rebuilding its reputation. Under his leadership, PANO launched programs like the "Give a Cop a Ticket to Safety" initiative, which provided over 1,000 bulletproof vests, and began publishing The Force, a respected magazine. PANO also established a legal defense fund, offering robust representation to officers facing disciplinary actions.

Advocacy and Legal Victories

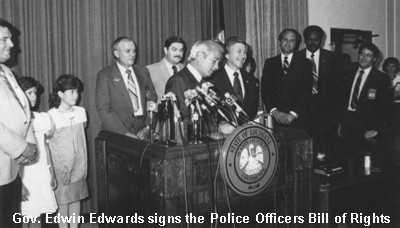

Throughout the 1980s, PANO fought numerous legal battles to secure fair treatment for its members. A landmark win came in the form of the Police Officers Bill of Rights, signed into law in 1985 after a five-year campaign. This legislation guaranteed constitutional protections for officers under investigation. PANO also successfully litigated overtime pay disputes, ultimately recovering $10.2 million in compensation for officers.

The union became increasingly active on the national stage, affiliating with the National Association of Police Organizations (NAPO) in 1984. This partnership amplified PANO’s influence, making it a prominent voice in law enforcement advocacy.

Challenges and Perseverance

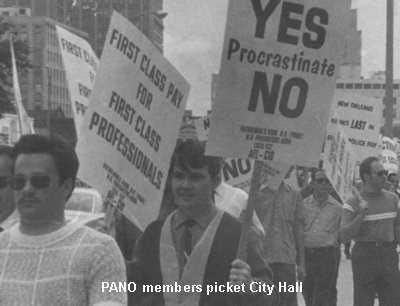

PANO faced its share of setbacks, including Mayor Sidney Barthelemy’s refusal to grant collective bargaining rights to police officers. However, the union maintained pressure through protests, informational campaigns, and collaboration with other police organizations. In 1988, PANO led a symbolic boycott of the Annual Inspection, with over 500 officers gathering in protest at Washington Artillery Park.

Financial struggles also tested the union’s resilience. Officers endured pay cuts, reduced work hours, and battles over state supplemental pay. Yet, PANO’s advocacy efforts, including a "Pay Police Like Your Life Depends On It" campaign, kept the pressure on city leaders.

Legacy and Looking Forward

By its 25th anniversary in 1994, PANO had firmly established itself as a champion of police officers’ rights. The union honored its founders and past leaders while reaffirming its commitment to representing “New Orleans’ Finest.” Through decades of challenges and triumphs, PANO has remained steadfast in its mission to support the men and women of the New Orleans Police Department.

PANO’s history is a testament to the power of unity and perseverance. As it continues into the 21st century, the union remains a vital force for change, advocating for the rights, safety, and dignity of New Orleans police officers.